Code

data <- read.csv("filepath/filename.csv")R ScriptR Markdown (.Rmd) File==!=><>=<=%in%%ni%is.na()!is.na()&|Importing data takes syntax of the following form for .csv files:

data <- read.csv("filepath/filename.csv")Note: it is important to use forward slashes (“/”) rather than backslashes (“\”) when specifying filepaths in R.

Below, I import a .csv file and save it into an object called mydata (you could call this object whatever you want):

mydata <- read.csv("https://osf.io/s6wrm/download")Importing data takes syntax of the following form for .RData files:

load("filepath/filename.RData")dataNames <- paste("data", 1:100, sep = "")

dataFilenames <- paste(dataNames, ".csv", sep = "")

dataFilepaths <- paste("C:/users/username/", dataFilenames, sep = "")

data_list <- lapply(dataFilepaths, read.csv) # lapply(dataFilepaths, data.table::fread) is even faster

names(data_list) <- basename(dataFilepaths)Alternatively, if you want to load all .csv files in a directory, you can identify the filenames programmatically:

dataFilenames <- list.files(

path = "C:/users/username/",

pattern = "\\.csv$")

dataFilepaths <- list.files(

path = "C:/users/username/",

pattern = "\\.csv$",

full.names = TRUE)

data_list <- lapply(dataFilepaths, read.csv) # lapply(dataFilepaths, data.table::fread) is even faster

names(data_list) <- basename(dataFilepaths)Saving data takes syntax of the following form for .csv files:

write.csv(object, file = "filepath/filename.csv")For example:

write.csv(mydata, file = "mydata.csv")Saving data takes syntax of the following form for .RData files:

save(object, file = "filepath/filename.RData")To use lab functions, first install the petersenlab package. The petersenlab package is here: https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab. You can install it using the following commands:

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("DevPsyLab/petersenlab")Once you have the petersenlab package installed, load the package:

To run scripts on the lab drive, set the path to the lab drive (//lc-rs-store24.hpc.uiowa.edu/lss_itpetersen/Lab/) using the following code:

petersenLabPath <- setLabPath()To install a single package that is on the CRAN repository, use the following syntax:

install.packages("name_of_package")To install multiple packages that are on the CRAN repository, use the following syntax:

install.packages(c("name_of_package1","name_of_package2","name_of_package3"))To install a package that is on a GitHub repository, use the following syntax:

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("username_of_GitHub_author/name_of_package")For instance:

remotes::install_github("DevPsyLab/petersenlab")The default way to load a package in R is:

However, when sourcing (i.e., running) other R scripts, it is possible that you will run scripts that use packages that you do not have installed, resulting in an error that prevents the script from running. Thus, it can be safer to load packages using the lab function, load_or_install(), rather than using library(). The load_or_install() function checks whether a package is installed. If the package is not installed, the function installs and loads the package. If the package is installed, the function loads the package. To use this function, you must have the petersenlab package loaded.

library("petersenlab")

load_or_install(c("packageName1","packageName2","packageName3"))For example:

library("petersenlab")

load_or_install(c("tidyverse","psych"))Set a seed (any number) to reproduce the results of analyses that involve random number generation.

set.seed(52242)R ScriptTo run an R script, use the following syntax:

source("filepath/filename.R")R Markdown (.Rmd) FileTo render a .Rmd file, use the following syntax:

render("filepath/filename.Rmd")To look at the names of variables in a data frame, use the following syntax:

names(mydata)[1] "survived" "pclass" "sex" "age" "sibsp"

[6] "parch" "prediction"Logical operators evaluate a condition for each value and yield values of TRUE and FALSE, corresponding to whether the evaluation for a given value met the condition.

==

mydata$survived == 1[1] TRUE TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE!=

mydata$survived != 1[1] FALSE FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE>

mydata$parch > 1[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE<

mydata$parch < 1[1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE>=

mydata$parch >= 1[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE<=

mydata$parch <= 1[1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE%in%

[1] TRUE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE TRUE%ni%

Note: this function is part of the petersenlab package and is not available in base R.

mydata$parch %ni% anotherVector[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSEis.na()

is.na(mydata$prediction)[1] FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE FALSE!is.na()

!is.na(mydata$prediction)[1] TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE&

!is.na(mydata$prediction) & mydata$parch >= 1[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSE|

is.na(mydata$prediction) | mydata$parch >= 1[1] FALSE TRUE TRUE TRUE TRUE FALSEWe can use the construction, if()...else if()...else() if we want to perform conditional operations. The typical construction of if()...else if()...else() operates such that it first checks if the first if() condition is true. If the first if() condition is true, it performs the operation specified and terminates the process. If the first if() condition is not true, it checks the else if() conditions in order until one of them is true. For the first true else if() condition, it performs the operation specified and terminates the process. If none of the else if() conditions is true, it performs the operation specified under else() and then terminates the process. The construction, if()...else if()...else() can only be used on one value at a time.

score <- 15

if(score <= 10){ # check this condition first

rank <- 1

print(rank)

} else if(score <= 20){ # if first condition was not met, check this condition next

rank <- 2

print(rank)

} else if(score <= 30){ # if first condition was not met, check this condition next

rank <- 3

print(rank)

} else{ # if all other conditions were not met, then do this

print("Not Applicable!")

}[1] 2To apply conditional operations to a vector, we can use the ifelse() function.

To subset a data frame, use brackets to specify the subset of rows and columns to keep, where the value/vector before the comma specifies the rows to keep, and the value/vector after the comma specifies the columns to keep:

dataframe[rowsToKeep, columnsToKeep]You can subset by using any of the following:

TRUE and FALSE corresponding to which rows/columns to keepTo subset one variable, use the following syntax:

mydata$age[1] 29.00 0.92 2.00 30.00 25.00 48.00or:

mydata[,"age"][1] 29.00 0.92 2.00 30.00 25.00 48.00To subset one variable, use the following syntax:

mydata$age[which(mydata$survived == 1)][1] 29.00 0.92 48.00 63.00 53.00 18.00or:

mydata[which(mydata$survived == 1), "age"][1] 29.00 0.92 48.00 63.00 53.00 18.00To subset particular columns/variables, use the following syntax:

R

Or, to drop columns:

mydata %>%

select(survived, age, prediction)mydata %>%

select(survived:prediction)mydata %>%

select(all_of(subsetVars))Or, to drop columns:

mydata %>%

select(-sibsp, -parch)mydata %>%

select(-c(sibsp:parch))mydata %>%

select(-all_of(dropVars))To subset particular rows, use the following syntax:

R

To subset particular rows and columns, use the following syntax:

R

mydata %>%

filter(survived == 1) %>%

select(all_of(subsetVars))To view data, use the following syntax:

View(mydata)To view only the first six rows (if a data frame) or elements (if a vector), use the following syntax:

mydata %>%

arrange(survived, age) #sort by survived (ascending) then by age (ascending)mydata %>%

arrange(survived, -age) #sort by survived (ascending) then by age (descending)str(mydata)'data.frame': 1046 obs. of 7 variables:

$ survived : int 1 1 0 0 0 1 1 0 1 0 ...

$ pclass : int 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 ...

$ sex : chr "female" "male" "female" "male" ...

$ age : num 29 0.92 2 30 25 48 63 39 53 71 ...

$ sibsp : int 0 1 1 1 1 0 1 0 2 0 ...

$ parch : int 0 2 2 2 2 0 0 0 0 0 ...

$ prediction: num 0.945 0.784 0.979 0.516 0.946 ...Number of rows and columns:

dim(mydata)[1] 1046 7length(mydata$age)[1] 1046To create a new variable, use the following syntax:

mydata$newVar <- NAHere is an example of creating a new variable:

mydata$ID <- 1:nrow(mydata)Here is an example of creating a data frame:

mydata2 <- data.frame(

ID = c(1:5, 1047:1051),

cat = sample(0:1, 10, replace = TRUE)

)

mydata2Here is an example of recoding a variable:

Recode multiple variables:

mydata <- mydata %>%

rename(

newVar1 = oldVar1,

newVar2 = oldVar2)Using a vector of variable names:

One variable:

mydata$factorVar <- factor(mydata$sex)

mydata$numericVar <- as.numeric(mydata$prediction)

mydata$integerVar <- as.integer(mydata$parch)

mydata$characterVar <- as.character(mydata$sex)Multiple variables:

mydata %>%

mutate(across(c(

age,

parch,

prediction),

as.numeric))mydata %>%

mutate(across(

age:parch,

as.numeric))mydata %>%

mutate(across(where(is.factor), as.character))Merging (also called joining) merges two data objects using a shared set of variables called “keys.” The keys are the variable(s) that uniquely identify each row (i.e., they account for the levels of nesting). In some data objects, the key might be the participant’s ID (e.g., participantID). However, some data objects have multiple keys. For instance, in long form data objects, each participant may have multiple rows corresponding to multiple timepoints. In this case, the keys are participantID and timepoint. If a participant has multiple rows corresponding to timepoints and measures, the keys are participantID, timepoint, and measure. In general, each row should have a value on each of the keys; there should be no missingness in the keys.

To merge two objects, the keys must be present in both objects. The keys are used to merge the variables in object 1 (x) with the variables in object 2 (y). Different merge types select different rows to merge.

Note: if the two objects include variables with the same name (apart from the keys), R will not know how you want each to appear in the merged object. So, it will add a suffix (e.g., .x, .y) to each common variable to indicate which object (i.e., object x or object y) the variable came from, where object x is the first object—i.e., the object to which object y (the second object) is merged. In general, apart from the keys, you should not include variables with the same name in two objects to be merged. To prevent this, either remove or rename the shared variable in one of the objects, or include the shared variable as a key. However, as described above, you should include it as a key only if it uniquely identifies each row in terms of levels of nesting.

Here are the data in the mydata object:

Here are the data in the mydata2 object:

Below is a visual that depicts various types of merges/joins. Object x is the circle labeled as A. Object y is the circle labeled as B. The area of overlap in the Venn diagram indicates the rows on the keys that are shared between the two objects (e.g., participantID values 1, 2, and 3). The non-overlapping area indicates the rows on the keys that are unique to each object (e.g., participantID values 4, 5, and 6 in Object x and values 7, 8, and 9 in Object y). The shaded yellow area indicates which rows (on the keys) are kept in the merged object from each of the two objects, when using each of the merge types. For instance, a left outer join keeps the shared rows and the rows that are unique to object x, but it drops the rows that are unique to object y.

Image source: Predictive Hacks (archived at: https://perma.cc/WV7U-BS68)

A full outer join includes all rows in \(x\) or \(y\). It returns columns from \(x\) and \(y\). Here is how to merge two data frames using a full outer join (i.e., “full join”):

fullJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all = TRUE)

fullJoinDatadim(fullJoinData)[1] 1051 15Or, alternatively, using tidyverse:

full_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")A left outer join includes all rows in \(x\). It returns columns from \(x\) and \(y\). Here is how to merge two data frames using a left outer join (“left join”):

leftJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.x = TRUE)

leftJoinDatadim(leftJoinData)[1] 1046 15Or, alternatively, using tidyverse:

left_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")A right outer join includes all rows in \(y\). It returns columns from \(x\) and \(y\). Here is how to merge two data frames using a right outer join (“right join”):

rightJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.y = TRUE)

rightJoinDatadim(rightJoinData)[1] 10 15Or, alternatively, using tidyverse:

right_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")An inner join includes all rows that are in both \(x\) and \(y\). An inner join will return one row of \(x\) for each matching row of \(y\), and can duplicate values of records on either side (left or right) if \(x\) and \(y\) have more than one matching record. It returns columns from \(x\) and \(y\). Here is how to merge two data frames using an inner join:

innerJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.x = FALSE, all.y = FALSE)

innerJoinDatadim(innerJoinData)[1] 5 15Or, alternatively, using tidyverse:

inner_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")A semi join is a filter. A left semi join returns all rows from \(x\) with a match in \(y\). That is, it filters out records from \(x\) that are not in \(y\). Unlike an inner join, a left semi join will never duplicate rows of \(x\), and it includes columns from only \(x\) (not from \(y\)). Here is how to merge two data frames using a left semi join:

semiJoinData <- semi_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

semiJoinDatadim(semiJoinData)[1] 5 14An anti join is a filter. A left anti join returns all rows from \(x\) without a match in \(y\). That is, it filters out records from \(x\) that are in \(y\). It returns columns from only \(x\) (not from \(y\)). Here is how to merge two data frames using a left anti join:

antiJoinData <- anti_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

antiJoinDatadim(antiJoinData)[1] 1041 14A cross join combines each row in \(x\) with each row in \(y\).

crossJoinData <- cross_join(

data.frame(rater = c("Mother","Father","Teacher")),

data.frame(timepoint = 1:3))

crossJoinDatadim(crossJoinData)[1] 9 2Original data:

fish_encountersData widened by a variable (station), using tidyverse:

fish_encounters %>%

pivot_wider(

names_from = station,

values_from = seen)Original data:

mtcarsData in long form, transformed from wide form using tidyverse:

mtcars %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value")Create data with multiple coders:

idWaveCoder <-

expand.grid(

id = 1:100,

wave = 1:3,

coder = 1:3,

positiveAffect = NA,

negativeAffect = NA

)

idWaveCoder$positiveAffect <- rnorm(nrow(idWaveCoder))

idWaveCoder$negativeAffect <- rnorm(nrow(idWaveCoder))

idWaveCoder %>%

arrange(id, wave, coder)Average data across coders:

idWave <- idWaveCoder %>%

group_by(id, wave) %>%

summarise(

across(everything(),

~ mean(.x, na.rm = TRUE)),

.groups = "drop") %>%

select(-coder)

idWaveIf you want to perform the same computation multiple times, it can be faster to do it in a loop compared to writing out the same computation many times. For instance, here is a loop that prints each element of a vector and the loop index (i) that indicates where the loop is in terms of its iterations:

[1] "The loop is at index: 1"

[1] "apple"

[1] "The loop is at index: 2"

[1] "banana"

[1] "The loop is at index: 3"

[1] "cherry"Now, let’s put together what we have learned to create a useful function. Functions are useful if you want to perform an operation multiple times. Any operation that you want to perform multiple times, you can create a function to accomplish. Use of a function can save you time without needed to retype out all of the code each time. For instance, let’s say you want to convert temperature between Fahrenheit and Celsius, you could create a function to do that. In this case, our function has two arguments: temperature (in degrees) and unit of the original temperature (F for Fahrenheit or C for Celsius, where the default unit is Fahrenheit).

convert_temperature <- function(temperature, unit = "F"){

if(unit == "F"){ # if the input temperature(s) in Fahrenheit

newtemp <- (temperature - 32) / (9/5)

} else if(unit == "C"){ # if the input temperature(s) in Celsius

newtemp <- (temperature * (9/5)) + 32

}

return(newtemp)

}Now we can use the function to convert temperatures between Fahrenheit and Celsius. A temperature of 32°F is equal to 0°C. A temperature of 0°C is equal to 89.6°F.

convert_temperature(

temperature = 32,

unit = "F"

)[1] 0convert_temperature(

temperature = 32,

unit = "C"

)[1] 89.6We can also convert the temperature for a vector of values at once:

convert_temperature(

temperature = c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50),

unit = "F"

)[1] -17.777778 -12.222222 -6.666667 -1.111111 4.444444 10.000000convert_temperature(

temperature = c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50),

unit = "C"

)[1] 32 50 68 86 104 122Because the default unit is “F”, we do not need to specify the unit if our input temperatures are in Fahrenheit:

convert_temperature(

c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50)

)[1] -17.777778 -12.222222 -6.666667 -1.111111 4.444444 10.000000R version 4.5.2 (2025-10-31)

Platform: x86_64-pc-linux-gnu

Running under: Ubuntu 24.04.3 LTS

Matrix products: default

BLAS: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libblas.so.3

LAPACK: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/openblas-pthread/libopenblasp-r0.3.26.so; LAPACK version 3.12.0

locale:

[1] LC_CTYPE=C.UTF-8 LC_NUMERIC=C LC_TIME=C.UTF-8

[4] LC_COLLATE=C.UTF-8 LC_MONETARY=C.UTF-8 LC_MESSAGES=C.UTF-8

[7] LC_PAPER=C.UTF-8 LC_NAME=C LC_ADDRESS=C

[10] LC_TELEPHONE=C LC_MEASUREMENT=C.UTF-8 LC_IDENTIFICATION=C

time zone: UTC

tzcode source: system (glibc)

attached base packages:

[1] stats graphics grDevices utils datasets methods base

other attached packages:

[1] psych_2.6.1 lubridate_1.9.5 forcats_1.0.1 stringr_1.6.0

[5] dplyr_1.2.0 purrr_1.2.1 readr_2.2.0 tidyr_1.3.2

[9] tibble_3.3.1 ggplot2_4.0.2 tidyverse_2.0.0 petersenlab_1.2.3

loaded via a namespace (and not attached):

[1] tidyselect_1.2.1 viridisLite_0.4.3 farver_2.1.2

[4] S7_0.2.1 fastmap_1.2.0 digest_0.6.39

[7] rpart_4.1.24 timechange_0.4.0 lifecycle_1.0.5

[10] cluster_2.1.8.1 magrittr_2.0.4 compiler_4.5.2

[13] rlang_1.1.7 Hmisc_5.2-5 tools_4.5.2

[16] yaml_2.3.12 data.table_1.18.2.1 knitr_1.51

[19] htmlwidgets_1.6.4 mnormt_2.1.2 plyr_1.8.9

[22] RColorBrewer_1.1-3 foreign_0.8-90 withr_3.0.2

[25] nnet_7.3-20 grid_4.5.2 stats4_4.5.2

[28] lavaan_0.6-21 xtable_1.8-8 colorspace_2.1-2

[31] scales_1.4.0 MASS_7.3-65 cli_3.6.5

[34] mvtnorm_1.3-3 rmarkdown_2.30 reformulas_0.4.4

[37] generics_0.1.4 otel_0.2.0 rstudioapi_0.18.0

[40] reshape2_1.4.5 tzdb_0.5.0 minqa_1.2.8

[43] DBI_1.3.0 splines_4.5.2 parallel_4.5.2

[46] base64enc_0.1-6 mitools_2.4 vctrs_0.7.1

[49] boot_1.3-32 Matrix_1.7-4 jsonlite_2.0.0

[52] hms_1.1.4 Formula_1.2-5 htmlTable_2.4.3

[55] glue_1.8.0 nloptr_2.2.1 stringi_1.8.7

[58] gtable_0.3.6 quadprog_1.5-8 lme4_2.0-1

[61] pillar_1.11.1 htmltools_0.5.9 R6_2.6.1

[64] Rdpack_2.6.6 mix_1.0-13 evaluate_1.0.5

[67] pbivnorm_0.6.0 lattice_0.22-7 rbibutils_2.4.1

[70] backports_1.5.0 Rcpp_1.1.1 gridExtra_2.3

[73] nlme_3.1-168 checkmate_2.3.4 xfun_0.56

[76] pkgconfig_2.0.3 ---

title: "Data Management"

---

# Import Data {#sec-importData}

Importing data takes syntax of the following form for `.csv` files:

```{r}

#| eval: false

data <- read.csv("filepath/filename.csv")

```

Note: it is important to use forward slashes ("/") rather than backslashes ("\\") when specifying filepaths in `R`.

Below, I import a `.csv` file and save it into an object called `mydata` (you could call this object whatever you want):

```{r}

#| eval: false

mydata <- read.csv("https://osf.io/s6wrm/download")

```

```{r}

#| include: false

mydata <- read.csv("./data/titanic.csv") #https://osf.io/s6wrm/download

```

Importing data takes syntax of the following form for `.RData` files:

```{r}

#| eval: false

load("filepath/filename.RData")

```

## Import Multiple Data Files {#sec-importMultipleDataFiles}

```{r}

#| eval: false

dataNames <- paste("data", 1:100, sep = "")

dataFilenames <- paste(dataNames, ".csv", sep = "")

dataFilepaths <- paste("C:/users/username/", dataFilenames, sep = "")

data_list <- lapply(dataFilepaths, read.csv) # lapply(dataFilepaths, data.table::fread) is even faster

names(data_list) <- basename(dataFilepaths)

```

Alternatively, if you want to load all `.csv` files in a directory, you can identify the filenames programmatically:

```{r}

#| eval: false

dataFilenames <- list.files(

path = "C:/users/username/",

pattern = "\\.csv$")

dataFilepaths <- list.files(

path = "C:/users/username/",

pattern = "\\.csv$",

full.names = TRUE)

data_list <- lapply(dataFilepaths, read.csv) # lapply(dataFilepaths, data.table::fread) is even faster

names(data_list) <- basename(dataFilepaths)

```

# Save Data {#sec-saveData}

Saving data takes syntax of the following form for `.csv` files:

```{r}

#| eval: false

write.csv(object, file = "filepath/filename.csv")

```

For example:

```{r}

#| eval: false

write.csv(mydata, file = "mydata.csv")

```

Saving data takes syntax of the following form for `.RData` files:

```{r}

#| eval: false

save(object, file = "filepath/filename.RData")

```

# Use Lab Functions {#sec-labFunctions}

To use lab functions, first install the [`petersenlab` package](https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab).

The [`petersenlab` package](https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab) is here: <https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab>.

You can install it using the following commands:

```{r}

#| eval: false

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("DevPsyLab/petersenlab")

```

Once you have the [`petersenlab` package](https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab) installed, load the package:

```{r}

library("petersenlab")

```

To run scripts on the lab drive, set the path to the lab drive (`//lc-rs-store24.hpc.uiowa.edu/lss_itpetersen/Lab/`) using the following code:

```{r}

#| eval: false

petersenLabPath <- setLabPath()

```

# Load/Install Packages {#sec-loadInstallPackages}

To install a single package that is on the CRAN repository, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

install.packages("name_of_package")

```

To install multiple packages that are on the CRAN repository, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

install.packages(c("name_of_package1","name_of_package2","name_of_package3"))

```

To install a package that is on a `GitHub` repository, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

install.packages("remotes")

remotes::install_github("username_of_GitHub_author/name_of_package")

```

For instance:

```{r}

#| eval: false

remotes::install_github("DevPsyLab/petersenlab")

```

The default way to load a package in `R` is:

```{r}

#| eval: false

library("packageName1")

library("packageName2")

library("packageName3")

```

However, when sourcing (i.e., running) other `R` scripts, it is possible that you will run scripts that use packages that you do not have installed, resulting in an error that prevents the script from running.

Thus, it can be safer to load packages using the lab function, `load_or_install(),` rather than using `library()`.

The `load_or_install()` function checks whether a package is installed.

If the package is not installed, the function installs and loads the package.

If the package is installed, the function loads the package.

To use this function, you must have the [`petersenlab` package](https://devpsylab.github.io/petersenlab) loaded.

```{r}

#| eval: false

library("petersenlab")

load_or_install(c("packageName1","packageName2","packageName3"))

```

For example:

```{r}

library("petersenlab")

load_or_install(c("tidyverse","psych"))

```

# Set a Seed {#sec-seed}

Set a seed (any number) to reproduce the results of analyses that involve random number generation.

```{r}

set.seed(52242)

```

# Run an `R` Script {#sec-source}

To run an `R` script, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

source("filepath/filename.R")

```

# Render an `R` Markdown (`.Rmd`) File {#sec-renderRmd}

To render a `.Rmd` file, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

render("filepath/filename.Rmd")

```

# Variable Names {#sec-varNames}

To look at the names of variables in a data frame, use the following syntax:

```{r}

names(mydata)

```

# Logical Operators {#sec-logicalOperators}

Logical operators evaluate a condition for each value and yield values of `TRUE` and `FALSE`, corresponding to whether the evaluation for a given value met the condition.

## Is Equal To: `==`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$survived == 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$survived == 1)

```

## Is Not Equal To: `!=`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$survived != 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$survived != 1)

```

## Greater Than: `>`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$parch > 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch > 1)

```

## Less Than: `<`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$parch < 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch < 1)

```

## Greater Than or Equal To: `>=`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$parch >= 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch >= 1)

```

## Less Than or Equal To: `<=`

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$parch <= 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch <= 1)

```

## Is in a Value of Another Vector: `%in%`

```{r}

#| output: false

anotherVector <- c(0,1)

mydata$parch %in% anotherVector

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch %in% anotherVector)

```

## Is Not in a Value of Another Vector: `%ni%`

Note: this function is part of the [`petersenlab`](https://github.com/DevPsyLab/petersenlab) package and is not available in base `R`.

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$parch %ni% anotherVector

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$parch %ni% anotherVector)

```

## Is Missing: `is.na()`

```{r}

#| output: false

is.na(mydata$prediction)

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(is.na(mydata$prediction))

```

## Is Not Missing: `!is.na()`

```{r}

#| output: false

!is.na(mydata$prediction)

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(!is.na(mydata$prediction))

```

## And: `&`

```{r}

#| output: false

!is.na(mydata$prediction) & mydata$parch >= 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(!is.na(mydata$prediction) & mydata$parch >= 1)

```

## Or: `|`

```{r}

#| output: false

is.na(mydata$prediction) | mydata$parch >= 1

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(is.na(mydata$prediction) | mydata$parch >= 1)

```

# If...Else Conditions {#sec-ifelse}

We can use the construction, `if()...else if()...else()` if we want to perform conditional operations.

The typical construction of `if()...else if()...else()` operates such that it first checks if the first `if()` condition is true.

If the first `if()` condition is true, it performs the operation specified and terminates the process.

If the first `if()` condition is not true, it checks the `else if()` conditions in order until one of them is true.

For the first true `else if()` condition, it performs the operation specified and terminates the process.

If none of the `else if()` conditions is true, it performs the operation specified under `else()` and then terminates the process.

The construction, `if()...else if()...else()` can only be used on one value at a time.

```{r}

score <- 15

if(score <= 10){ # check this condition first

rank <- 1

print(rank)

} else if(score <= 20){ # if first condition was not met, check this condition next

rank <- 2

print(rank)

} else if(score <= 30){ # if first condition was not met, check this condition next

rank <- 3

print(rank)

} else{ # if all other conditions were not met, then do this

print("Not Applicable!")

}

```

To apply conditional operations to a vector, we can use the `ifelse()` function.

```{r}

score <- c(1, 10, 20, 40, 100)

rank <- ifelse(

score <= 10, # check this condition

1, # assign this value if true

2) # assign this value if false

rank

```

# Subset {#sec-subset}

To subset a data frame, use brackets to specify the subset of rows and columns to keep, where the value/vector before the comma specifies the rows to keep, and the value/vector after the comma specifies the columns to keep:

```{r}

#| eval: false

dataframe[rowsToKeep, columnsToKeep]

```

You can subset by using any of the following:

- numeric indices of the rows/columns to keep (or drop)

- names of the rows/columns to keep (or drop)

- values of `TRUE` and `FALSE` corresponding to which rows/columns to keep

## One Variable

To subset one variable, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$age

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$age)

```

or:

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata[,"age"]

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata[,"age"])

```

## Particular Rows of One Variable

To subset one variable, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata$age[which(mydata$survived == 1)]

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata$age[which(mydata$survived == 1)])

```

or:

```{r}

#| output: false

mydata[which(mydata$survived == 1), "age"]

```

```{r}

#| echo: false

head(mydata[which(mydata$survived == 1), "age"])

```

## Particular Columns (Variables)

To subset particular columns/variables, use the following syntax:

### Base `R`

```{r}

subsetVars <- c("survived","age","prediction")

mydata[,c(1,2,3)]

mydata[,c("survived","age","prediction")]

mydata[,subsetVars]

```

Or, to drop columns:

```{r}

dropVars <- c("sibsp","parch")

mydata[,-c(5,6)]

mydata[,names(mydata) %ni% c("sibsp","parch")]

mydata[,names(mydata) %ni% dropVars]

```

### Tidyverse

```{r}

mydata %>%

select(survived, age, prediction)

mydata %>%

select(survived:prediction)

mydata %>%

select(all_of(subsetVars))

```

Or, to drop columns:

```{r}

mydata %>%

select(-sibsp, -parch)

mydata %>%

select(-c(sibsp:parch))

mydata %>%

select(-all_of(dropVars))

```

## Particular Rows

To subset particular rows, use the following syntax:

### Base `R`

```{r}

subsetRows <- c(1,3,5)

mydata[c(1,3,5),]

mydata[subsetRows,]

mydata[which(mydata$survived == 1),]

```

### Tidyverse

```{r}

mydata %>%

filter(survived == 1)

mydata %>%

filter(survived == 1, parch <= 1)

mydata %>%

filter(survived == 1 | parch <= 1)

```

## Particular Rows and Columns

To subset particular rows and columns, use the following syntax:

### Base `R`

```{r}

mydata[c(1,3,5), c(1,2,3)]

mydata[subsetRows, subsetVars]

mydata[which(mydata$survived == 1), subsetVars]

```

### Tidyverse

```{r}

mydata %>%

filter(survived == 1) %>%

select(all_of(subsetVars))

```

# View Data {#sec-viewData}

## All Data

To view data, use the following syntax:

```{r}

#| eval: false

View(mydata)

```

## First 6 Rows/Elements

To view only the first six rows (if a data frame) or elements (if a vector), use the following syntax:

```{r}

head(mydata)

head(mydata$age)

```

# Sort Data {#sec-sortData}

```{r}

mydata %>%

arrange(survived, age) #sort by survived (ascending) then by age (ascending)

mydata %>%

arrange(survived, -age) #sort by survived (ascending) then by age (descending)

```

# Data Characteristics {#sec-dataCharacteristics}

## Data Structure

```{r}

str(mydata)

```

## Data Dimensions

Number of rows and columns:

```{r}

dim(mydata)

```

## Number of Elements

```{r}

length(mydata$age)

```

## Number of Missing Elements

```{r}

length(mydata$age[which(is.na(mydata$age))])

```

## Number of Non-Missing Elements

```{r}

length(mydata$age[which(!is.na(mydata$age))])

length(na.omit(mydata$age))

```

# Create New Variables {#sec-createNewVars}

To create a new variable, use the following syntax:

```{r}

mydata$newVar <- NA

```

```{r}

#| include: false

mydata$newVar <- NULL

```

Here is an example of creating a new variable:

```{r}

mydata$ID <- 1:nrow(mydata)

```

# Create a Data Frame {#sec-createDF}

Here is an example of creating a data frame:

```{r}

mydata2 <- data.frame(

ID = c(1:5, 1047:1051),

cat = sample(0:1, 10, replace = TRUE)

)

mydata2

```

# Recode Variables {#sec-recodeVars}

Here is an example of recoding a variable:

```{r}

mydata$oldVar1[which(mydata$sex == "male")] <- 0

mydata$oldVar1[which(mydata$sex == "female")] <- 1

mydata$oldVar2[which(mydata$sex == "male")] <- 1

mydata$oldVar2[which(mydata$sex == "female")] <- 0

```

Recode multiple variables:

```{r}

mydata %>%

mutate(across(c(

survived:pclass),

~ case_match(

.,

0 ~ "No",

1 ~ "Yes")))

mydata %>%

mutate(across(c(

survived:pclass),

~ case_match(

.,

c(0,1) ~ 1,

c(2,3) ~ 2)))

```

# Rename Variables {#sec-renameVars}

```{r}

mydata <- mydata %>%

rename(

newVar1 = oldVar1,

newVar2 = oldVar2)

```

Using a vector of variable names:

```{r}

#| eval: false

varNamesFrom <- c("oldVar1","oldVar2")

varNamesTo <- c("newVar1","newVar2")

mydata <- mydata %>%

rename_with(~ varNamesTo, all_of(varNamesFrom))

```

# Convert the Types of Variables {#sec-convertVarTypes}

One variable:

```{r}

mydata$factorVar <- factor(mydata$sex)

mydata$numericVar <- as.numeric(mydata$prediction)

mydata$integerVar <- as.integer(mydata$parch)

mydata$characterVar <- as.character(mydata$sex)

```

Multiple variables:

```{r}

mydata %>%

mutate(across(c(

age,

parch,

prediction),

as.numeric))

mydata %>%

mutate(across(

age:parch,

as.numeric))

mydata %>%

mutate(across(where(is.factor), as.character))

```

# Merging/Joins {#sec-merging}

## Overview

Merging (also called joining) merges two data objects using a shared set of variables called "keys."

The keys are the variable(s) that uniquely identify each row (i.e., they account for the levels of nesting).

In some data objects, the key might be the participant's ID (e.g., `participantID`).

However, some data objects have multiple keys.

For instance, in long form data objects, each participant may have multiple rows corresponding to multiple timepoints.

In this case, the keys are `participantID` and `timepoint`.

If a participant has multiple rows corresponding to timepoints and measures, the keys are `participantID`, `timepoint`, and `measure`.

In general, each row should have a value on each of the keys; there should be no missingness in the keys.

To merge two objects, the keys must be present in both objects.

The keys are used to merge the variables in object 1 (`x`) with the variables in object 2 (`y`).

Different merge types select different rows to merge.

Note: if the two objects include variables with the same name (apart from the keys), `R` will not know how you want each to appear in the merged object.

So, it will add a suffix (e.g., `.x`, `.y`) to each common variable to indicate which object (i.e., object `x` or object `y`) the variable came from, where object `x` is the first object—i.e., the object to which object `y` (the second object) is merged.

In general, apart from the keys, you should not include variables with the same name in two objects to be merged.

To prevent this, either remove or rename the shared variable in one of the objects, or include the shared variable as a key.

However, as described above, you should include it as a key ***only*** if it uniquely identifies each row in terms of levels of nesting.

## Data Before Merging

Here are the data in the `mydata` object:

```{r}

mydata

dim(mydata)

```

Here are the data in the `mydata2` object:

```{r}

mydata2

dim(mydata2)

```

## Types of Joins {#sec-mergeTypes}

### Visual Overview of Join Types

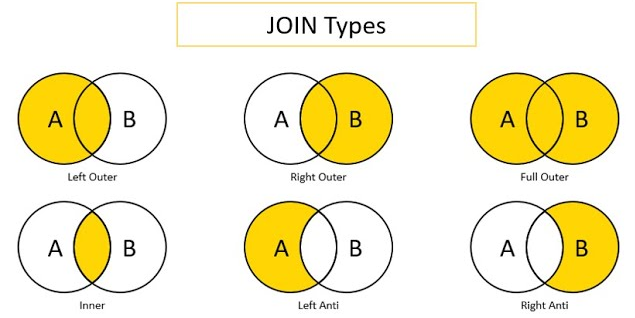

Below is a visual that depicts various types of merges/joins.

Object `x` is the circle labeled as `A`.

Object `y` is the circle labeled as `B`.

The area of overlap in the Venn diagram indicates the rows on the keys that are shared between the two objects (e.g., `participantID` values 1, 2, and 3).

The non-overlapping area indicates the rows on the keys that are unique to each object (e.g., `participantID` values 4, 5, and 6 in Object `x` and values 7, 8, and 9 in Object `y`).

The shaded yellow area indicates which rows (on the keys) are kept in the merged object from each of the two objects, when using each of the merge types.

For instance, a left outer join keeps the shared rows and the rows that are unique to object `x`, but it drops the rows that are unique to object `y`.

Image source: [Predictive Hacks](https://predictivehacks.com/?all-tips=anti-joins-with-pandas) (archived at: <https://perma.cc/WV7U-BS68>)

### Full Outer Join {#sec-fullJoin}

A full outer join includes all rows in $x$ **or** $y$.

It returns columns from $x$ and $y$.

Here is how to merge two data frames using a full outer join (i.e., "full join"):

```{r}

fullJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all = TRUE)

fullJoinData

dim(fullJoinData)

```

Or, alternatively, using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

full_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

```

### Left Outer Join {#sec-leftJoin}

A left outer join includes all rows in $x$.

It returns columns from $x$ and $y$.

Here is how to merge two data frames using a left outer join ("left join"):

```{r}

leftJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.x = TRUE)

leftJoinData

dim(leftJoinData)

```

Or, alternatively, using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

left_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

```

### Right Outer Join {#sec-rightJoin}

A right outer join includes all rows in $y$.

It returns columns from $x$ and $y$.

Here is how to merge two data frames using a right outer join ("right join"):

```{r}

rightJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.y = TRUE)

rightJoinData

dim(rightJoinData)

```

Or, alternatively, using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

right_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

```

### Inner Join {#sec-innerJoin}

An inner join includes all rows that are in **both** $x$ **and** $y$.

An inner join will return one row of $x$ for each matching row of $y$, and can duplicate values of records on either side (left or right) if $x$ and $y$ have more than one matching record.

It returns columns from $x$ and $y$.

Here is how to merge two data frames using an inner join:

```{r}

innerJoinData <- merge(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID", all.x = FALSE, all.y = FALSE)

innerJoinData

dim(innerJoinData)

```

Or, alternatively, using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

inner_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

```

### Semi Join {#sec-semiJoin}

A semi join is a filter.

A left semi join returns all rows from $x$ **with** a match in $y$.

That is, it filters out records from $x$ that are not in $y$.

Unlike an [inner join](#sec-innerJoin), a left semi join will never duplicate rows of $x$, and it includes columns from only $x$ (not from $y$).

Here is how to merge two data frames using a left semi join:

```{r}

semiJoinData <- semi_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

semiJoinData

dim(semiJoinData)

```

### Anti Join {#sec-antiJoin}

An anti join is a filter.

A left anti join returns all rows from $x$ **without** a match in $y$.

That is, it filters out records from $x$ that are in $y$.

It returns columns from only $x$ (not from $y$).

Here is how to merge two data frames using a left anti join:

```{r}

antiJoinData <- anti_join(mydata, mydata2, by = "ID")

antiJoinData

dim(antiJoinData)

```

### Cross Join {#sec-crossJoin}

A cross join combines each row in $x$ with each row in $y$.

```{r}

crossJoinData <- cross_join(

data.frame(rater = c("Mother","Father","Teacher")),

data.frame(timepoint = 1:3))

crossJoinData

dim(crossJoinData)

```

# Long to Wide {#sec-longToWide}

Original data:

```{r}

fish_encounters

```

Data widened by a variable (`station`), using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

fish_encounters %>%

pivot_wider(

names_from = station,

values_from = seen)

```

# Wide to Long {#sec-wideToLong}

Original data:

```{r}

mtcars

```

Data in long form, transformed from wide form using `tidyverse`:

```{r}

mtcars %>%

pivot_longer(

cols = everything(),

names_to = "variable",

values_to = "value")

```

# Average Ratings Across Coders {#sec-avgAcrossCoders}

Create data with multiple coders:

```{r}

#| code-fold: true

idWaveCoder <-

expand.grid(

id = 1:100,

wave = 1:3,

coder = 1:3,

positiveAffect = NA,

negativeAffect = NA

)

idWaveCoder$positiveAffect <- rnorm(nrow(idWaveCoder))

idWaveCoder$negativeAffect <- rnorm(nrow(idWaveCoder))

idWaveCoder %>%

arrange(id, wave, coder)

```

Average data across coders:

```{r}

idWave <- idWaveCoder %>%

group_by(id, wave) %>%

summarise(

across(everything(),

~ mean(.x, na.rm = TRUE)),

.groups = "drop") %>%

select(-coder)

idWave

```

# Loops {#sec-loops}

If you want to perform the same computation multiple times, it can be faster to do it in a loop compared to writing out the same computation many times.

For instance, here is a loop that prints each element of a vector and the loop index (`i`) that indicates where the loop is in terms of its iterations:

```{r}

fruits <- c("apple", "banana", "cherry")

for(i in 1:length(fruits)){

print(paste("The loop is at index:", i, sep = " "))

print(fruits[i])

}

```

## Create a Function {#sec-createFunction}

Now, let's put together what we have learned to create a useful function.

Functions are useful if you want to perform an operation multiple times.

Any operation that you want to perform multiple times, you can create a function to accomplish.

Use of a function can save you time without needed to retype out all of the code each time.

For instance, let's say you want to convert temperature between Fahrenheit and Celsius, you could create a function to do that.

In this case, our function has two arguments: `temperature` (in degrees) and `unit` of the original temperature (`F` for Fahrenheit or `C` for Celsius, where the default unit is Fahrenheit).

```{r}

convert_temperature <- function(temperature, unit = "F"){

if(unit == "F"){ # if the input temperature(s) in Fahrenheit

newtemp <- (temperature - 32) / (9/5)

} else if(unit == "C"){ # if the input temperature(s) in Celsius

newtemp <- (temperature * (9/5)) + 32

}

return(newtemp)

}

```

Now we can use the function to convert temperatures between Fahrenheit and Celsius.

A temperature of 32°F is equal to 0°C.

A temperature of 0°C is equal to 89.6°F.

```{r}

convert_temperature(

temperature = 32,

unit = "F"

)

convert_temperature(

temperature = 32,

unit = "C"

)

```

We can also convert the temperature for a vector of values at once:

```{r}

convert_temperature(

temperature = c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50),

unit = "F"

)

convert_temperature(

temperature = c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50),

unit = "C"

)

```

Because the default unit is "F", we do not need to specify the unit if our input temperatures are in Fahrenheit:

```{r}

convert_temperature(

c(0, 10, 20, 30, 40, 50)

)

```

# Session Info

```{r}

#| code-fold: true

sessionInfo()

```